This article was published in the Times Union

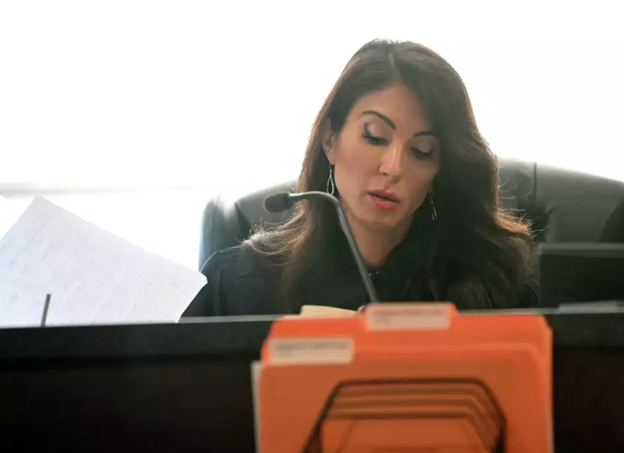

Judge Francine Vero presides over first homeless court in upstate New York

After spending the day panhandling and collecting discarded bottles and cans for cash, he would push his cart along the city’s sidewalks, seeking a safe and dry place to sleep. Then on the morning of May 15, Parks was ticketed for trespassing after he took refuge in the Woodlawn Avenue parking garage. The violation sent him to Saratoga Springs City Court where he faced Judge Francine Vero in her twice-monthly Community Outreach Court — a proceeding in which only those who are homeless appear.

Then on the morning of May 15, Parks was ticketed for trespassing after he took refuge in the Woodlawn Avenue parking garage. The violation sent him to Saratoga Springs City Court where he faced Judge Francine Vero in her twice-monthly Community Outreach Court — a proceeding in which only those who are homeless appear.

These offenses mostly include general violations of local law such as having an open alcoholic container or making noise, trespassing, disorderly conduct, obstructing governmental administration and petit larceny. The theory is that these crimes stem from their homelessness and therefore finding help for them reduces the nuisance crimes.

Vero established the court, with the blessing of then-Mayor Meg Kelly. Court only for the homeless population has only been seen in bigger cities like Los Angeles, Houston, Boston and Phoenix. At the time, Vero, who was unable to sit for a Times Union interview as rules for judges prohibit speaking with the media, told RISE she wanted to open the court because the same names appeared on her docket over and over.

“She said what the courts were doing wasn’t actually helpful or changing the behavior of the individuals or improving their lives,” Sybil Newell, RISE executive director, said. “She identified the need for a different approach.”

Al Baker, New York Office of Court Administration spokesman, said Vero recognized that many homeless people were “caught in a ‘revolving door’ with the criminal justice system in which they would offend, fail to appear in court, and then reoffend shortly thereafter.”

Baker said that ultimately it “negatively impacted the Saratoga Springs community, was a strain on resources and in no way served the affected population.”

At the arraignment for these nonviolent crimes, Vero refers the defendant to RISE in lieu of fines and jail time, Furfaro said. From there, RISE will get them a bed and help with everything from food stamps, birth certificates and drivers’ licenses, to vital medical, mental health and substance abuse treatments. RISE said it can diagnose problems and expedite a meaningful plan.

The program is voluntary. But over the past four years, RISE reported only nine people rejected the help. One reason, perhaps, is Vero is persuasive on the bench — telling defendants repeatedly that she wants them to be successful and that working with RISE could help them avoid the consequences of their actions.

“We have a lot of success stories,” Newell said. “Sometimes it takes a few times in court before it sticks. But we’ve gotten individuals connected to services.”

Vero’s court, however, is not a pass for the homeless to commit crimes. Those ordered to work with RISE must check in at least once a week, stay out of trouble, report any new police encounters and comply with all treatment plans.

In addition to helping defendants find a place to live, benefits and treatments, the RISE coordinator must keep track of all court appearances and provide the defendant with transportation to court, according to the state Office of Court Administration. The coordinator also must provide a status report to the Saratoga County district attorney’s office and the county public defender’s office so that the prosecutors and the public attorney ensure the defendant complied with all that was asked of them before charges can be dismissed.

“I think it is a very good program,” Newell said. “It has the ability to help us to address the visible street homeless that seems to be a big concern for Saratoga Springs. The police and court’s involvement in working with our street homeless population and putting them on a better path has made a huge difference in people congregating downtown.”

Saratoga Springs is a city that thrives on a tourism economy that many believe is blighted by homelessness. For years, downtown business owners have complained about people sleeping on benches or panhandling in front of their shops and eateries. Residents and downtown employees also spoke of their fear of the parking garages that once housed a number of people.

The number of people who would be classified as homeless in the Capital Region’s urban areas — and how they compare to each other — is difficult to track. The federal Department of Housing and Urban Development has estimated counts of people who are homeless each year, but each area the data covers is large. For example, Saratoga Springs is lumped in with Saratoga County, as well as Hamilton, Warren and Washington counties. Data from 2023 said 332 people were homeless in the Saratoga data set, compared to 430 for Schenectady city and county, 156 for Troy and Rensselaer County, and 889 for Albany city and county.

In recent election seasons, many candidates promise to get people off the streets of Saratoga Springs . But once they are in office, they find the problem intractable — mainly because solutions (such as subsidized and workforce housing as well as shelters) are fiercely opposed by residents who live in areas where these homes are proposed.

Some effective measures have been taken by nonprofits such as daily meals at the Presbyterian-United Church of Christ, free clothes and showers at the Salvation Army, the low-barrier Code Blue winter shelter run by Shelters of Saratoga, donation boxes on Broadway as well as assistance from many nonprofits including Healing Springs, Wellspring and CAPTAIN Community Human Service. City Commissioner of Public Safety Tim Coll also said he is working to hire a social worker to help police better deal with the homeless, which was one of the requirements of a 50-point police reform plan the City Council adopted in 2021.

However, since RISE opened a 24-7 low barrier shelter on Adelphi Street, the visibility of people downtown without permanent residences has decreased. The community outreach court, or homeless court as it is known, adds another layer to social supports.

But Sherie Grinter, a Red Cross volunteer who has been feeding about 20 people every Saturday in Congress Park for years, said the court can’t help everyone because a lot of the people who go to court do not trust the judicial system. She blames city police who she says often ticket and search people for yelling at police, sitting on a curb near the Woodlawn parking garage or sleeping on the sidewalk — things she believes should not be offenses.

Still, she sits through most of the court proceedings and said, “Judge Vero tries to help.” Grinter wishes the help could come before the trauma of tickets and arrests. However, the homeless court does “help with the population that is actually committing crimes,” she said.

Certainly, it’s not always easy for Vero to convince all of the defendants that the court is there to help.

On a recent visit to Vero’s court, one defendant who was charged with trespassing wanted to be sentenced to 15 days in jail “to get it over with.” She didn’t want to work with RISE because she works with homeless advocates in Glens Falls. Vero talked her out jail, telling her she could continue to work with Catholic Charities in Glens Falls and RISE would work with Catholic Charities to keep an eye on her remotely. The woman, who was distraught, finally agreed.

Vero also works with defendants who have ruined their chances to get help through RISE. For one defendant, who “had an incident” with RISE, Vero handed a list of things he must do in order to comply with a one-year conditional discharge on a harassment violation and a criminal tampering misdemeanor. Without RISE, he must monitor himself by remaining arrest free, staying away from his victim and continuing with mental health treatments. If he didn’t, the veteran could face felony charges, Vero warned.

She also urged him to continue with his mental health treatments, saying, “I don’t want to set him up for failure.”

The defendant, who occasionally sobbed in court, promised Vero “he exceeded all expectations” and has a place to live. Vero was understanding, but firm, adding she needs positive reports on his progress from a doctor.

Others on the docket didn’t come to court. Instead, RISE provided updates to the judge on their development — one with a trespassing charge was feeling ill and unable to come, another was in Saratoga County jail, another was doing well and there were no new arrests or tickets, and yet another person, with multiple arrests, has moved into treatment.

None of this would be possible without the buy-in from the Saratoga County district attorney’s office, whose staff must agree to referring the defendants to the care of RISE.

District Attorney Karen Heggen said the court is working well.

“It’s been quite effective, getting people to come to court, addressing their charges and getting themselves on a track. That has been helpful to them,” she said. “I give Judge Vero a lot of credit. She takes the time and energy and effort to understand the status of each of their cases.”

Mayor John Safford said he too supports the work of the court, calling it a “a positive thing for a good number of people who go through it.” But he remains skeptical because he said, “They get acclimated to the lifestyle and then it’s more difficult to change that lifestyle.”

He’s also uncertain of a separate program, RISE’s Housing First initiative, which gets people places to live while concurrently addressing their problems in court. Safford believes people should be sober before getting housing. Still, the city funds both RISE and the court, $300,000 and $80,000 a year, respectively.

Yet Grinter said people can’t think about getting sober or getting medical attention until they are settled in a home.

“If you get someone into housing first, a lot of their fears, feeling they are going to get attacked, ‘I have to sleep with one eye open, I’ve gotten everything stolen,’ finally go away,” Grinter said. “Now, you can get them a 28-day program and when they are released, they are back in a house not on the street.”

With housing first in mind, RISE also works on building more supportive and affordable housing, like the newly opened Dominic Hollow apartments in Ballston Spa. RISE spokeswoman Leanne Ricchiuti said one of the residents there has a history of petty crime and going through Vero’s court changed his life.

“He graduated the outreach court in July of 2023, but started living in Dominic Hollow in April 2023,” Rucchiuti said. “He previously had a very lengthy criminal history, but with the help of RISE, he’s been able to manage things easier. He’s a true success story.”

Parks, who recently was sitting on the side of the road along South Broadway with a sign asking for money, seemed optimistic at the prospects, too.

“I got bad legs and I got a tumor on my right lung and epilepsy,” Parks said. “Everything just went downhill so I’m stuck out here … Once I get a roof over my head, it will be good.”